Spratt enjoyed ‘formative’ time in Brandon

Courtesy of Perry Bergson, The Brandon Sun

Ron Spratt played his last hockey game in Brandon 53 years ago, but his warm memories of the city haven’t dimmed with age.

Now 73, Spratt spent a pair of seasons with the Wheat Kings from 1965 to 1967.

Ron Spratt is shown during his time with the Brandon Wheat Kings. (Brandon Sun file photo)

“I’ll never forget the two years in Brandon,” Spratt said. “They were formative years for me. The best years of my hockey career were in Brandon.”

Spratt was born in Moose Jaw but his family moved to North Battleford when he was six. Spratt was the oldest of three children, along with brother Len, who also played hockey, and sister Diane.

Ron first played organized games after the move. The sport had quickly become important to him and his friends.

“Everything was outdoors except for casual skating down at the arena,” Spratt said. “Everything else was on the street and school rinks. My dad used to build a rink for us every year in the backyard.”

With a big group of players his age, hockey became an obsession for Spratt and his friends.

“We played nonstop, especially out on the street because in those days it was so miserably cold,” Spratt said. “We would have 20 kids show up and throw their sticks in the centre, and we’d pick two teams and stay out there until dark.”

After his dad built the rink, they split their time between it and the road.

At an area rink, a caretaker kept the pot-bellied stove warm in the shack, and Spratt and his friends would shovel the ice and then skate.

He became a defenceman early, in large part due to the abundance of talent up front in the community, which was in Boston Bruins territory.

“North Battleford was a hotbed for hockey,” Spratt said. “A lot of professional hockey players came out of that town.”

His parents Ron Sr. and Violet made it all possible. Aside from providing equipment, they also served as frequent chauffeurs.

“They were very supportive,” Spratt said. “We had to travel to all locations — Rosetown, Saskatoon, every small town in the area — and back in those days with the snowstorms, my dad was always there making sure that we got to those games and that we got home safe.”

He played all of his minor hockey in North Battleford until he entered St. Thomas College boy’s school and played with them for three seasons.

They played against other local schools and colleges.

Spratt said junior hockey wasn’t really on his mind growing up. Instead, it was a much higher level.

Ron Spratt poses in a recent picture in a Brandon Wheat Kings T-shirt. Spratt played with the club for two seasons from 1965 to 1967. (Submitted)

“The only thing we ever thought about, because it was the holy grail in our house on Saturday night, was Hockey Night In Canada,” Spratt said. “We all watched it together. There was never any knowledge at that point in time of junior B. I played midget junior B, but after that to get into junior A or anything else like that was far from my thoughts. It was just playing the game and moving on as things permitted.”

After his final season at St. Thomas, Spratt signed with the Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League’s Estevan Bruins, who were coached by the legendary Scotty Munro, the namesake of the Western Hockey League’s trophy given to its regular season champion.

Although he was injured, Spratt attended their camp in the fall of 1965. He never played a game for the Bruins, however.

“How it happened to this day I still don’t know, but (Wheat Kings general manager and head coach) Eddie Dorohoy approached me and there were arrangements made between Scotty and Eddie and I was on my way to Brandon,” Spratt said.

He joined the Wheat Kings in training camp, a big step because he was suddenly 750 kilometres from home. He settled in with his new billets, Ruth and Russ Mummery, who played a major role in easing the transition.

Spratt admitted it was tough to adjust to the game on the ice.

“Probably the most difficult thing in my hockey career was not being mature enough to handle it,” Spratt said. “When I look back at my stats, my second year into wherever I played hockey was always the best. That first year going into junior A was a real learning curve, being away from home and starting to learn systems. Back in North Battleford, you’re a hockey star. You go and do what you want on to the ice and play I don’t know how many minutes.

“All of a sudden junior A comes along and there are systems and a whole new learning curve to the game, and you understand that it’s not the same game you played for fun out on the ice years and years and years ago. You’re now playing a different sport, so to speak.”

Spratt was paired with Bill Mikkelson in front of goalie Al Johnstone, but at the time, Brandon’s star power was up front.

The dynamic duo of Bill Fairbairn and Juha Widing was entering its second season with the Wheat Kings, with Erv Ziemer also on the line.

“Billy was our fearless leader,” Spratt said. “He went about his business in a very quiet way … but when he needed to take charge on the ice, he took charge. He just made us comfortable out there, whether it was getting into a fight or putting the puck in the net. He set an example for the rest of us.”

Spratt said he never forgot a moment on the bench when he was sitting beside Fairbairn as they played against future World Hockey Association player Fran Huck and the Regina Pats. Fairbairn, who would go on to score 162 goals in 658 games over 11 NHL seasons himself, was transfixed by Huck.

“This is how humble Billy was, because he was a helluva hockey player,” said Spratt, who Fairbairn called Sparky. “I remember him turning sideways to me and saying ‘You know Sparky, just think, here we are sitting in this box and we didn’t have to pay anything to get into this arena to watch this guy play.’ That’s how good Fran Huck was back in those days but Billy being as humble as he was, looked at everyone else as that much better.”

Pratt said Fairbairn, who was named an SJHL first-team all-star that season, is the hardest working player he ever skated with on the ice.

Widing was also a sight to behold. The Finnish-born forward, who grew up in Sweden and played eight NHL seasons, was known for his skating and skill.

“His skating ability was something that even Billy would say that we hadn’t seen before,” Spratt said. “When he took a stride it was amazing just to see and watch.”

Ziemer was the most unheralded member of the line, who Spratt said were all unassuming guys.

“Erv could set the plays up,” Spratt said. “He was a tireless worker on the ice.”

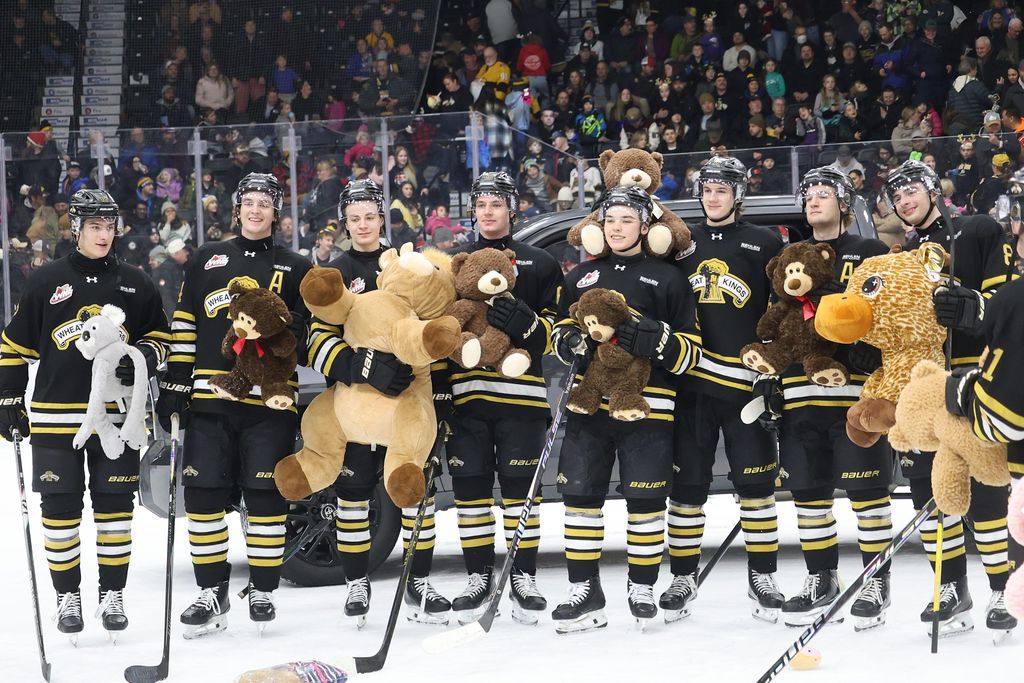

The 1966-67 Brandon Wheat Kings roster is featured in the Brandon Sun. The team made its return to the Manitoba Junior Hockey League that season. (Brandon Sun file)

Spratt said all three showed up to play the same way whether the game was in Brandon, Regina or the notoriously hostile environment in Flin Flon, where the Brandon bus needed a police escort to leave town on numerous occasions.

Johnstone was another team stalwart, playing all 60 games during the 1965-66 season.

“Al was married, and his wife was in Brandon with him,” Spratt said. “He was a great goaltender, he was our backstop. We never had to worry when he was in net. He was a great competitor.”

Dorohoy was another interesting character. The longtime pro hockey player coached two seasons in Brandon, with Spratt on his blue-line both years.

“I had a great connection with Eddie,” Spratt said. “He was the best coach I ever had. He was ‘The Pistol,’ that was his nickname. He treated everyone fairly on that team. He was a real mentor for me. He never ever would come down on you on the bench in front of the other players if you made a mistake. He just always came over and spoke to you about it and then put you back out on the ice right away. His coaching techniques were the best I ever had.”

The coach, who was in his mid-40s at the time, would sometimes take the puck during practice and challenge players to take it away from him, which wasn’t an easy task.

Spratt said it was a hard, physical game in the SJHL at the time but without many cheap shots.

“It was a tough brand of hockey but I don’t recall back in those days some of the stuff that went on later as far as the spearing and dirty checks,” Spratt said. “I don’t recall that ever happening to me. I recall going out and playing a hard 60 minutes of hockey against every one of the teams we played against at home and on the road. Yes, there were fights, and lots of them, but I don’t recall the dirty stuff that I saw years later.”

In his rookie season in 1965-66, Spratt led the club with 106 penalty minutes. While part of that was his hard-nosed play in front of the net, it included some fighting majors.

“I was a stay-at-home defenceman who prided myself on my skating ability,” Spratt said. “That role of taking care (of teammates) if I had to, I was ready to step to the plate and do what I thought was part of my role to play on that team.”

Spratt also added three goals — his first junior goal came on Dec. 5, 1965 in an 8-4 win over the Melville Millionaires — and 16 assists in 60 games.

Brandon beat the Saskatoon Blades 4-1 in the best-of-seven quarterfinal before falling 4-2 to the Weyburn Red Wings.

There was one massive change waiting for Spratt when he returned for his second season. After the 1965-66 season, the SJHL disbanded, beginning what proved to be a two-year hiatus. As a result, the Wheat Kings and Bombers moved over to the Manitoba Junior Hockey League.

“If you talked to the guys and they were honest, I don’t think any one of them knew what was going on,” Spratt said.

Spratt said there wasn’t much different about the actual hockey, although the road trips were usually shorter.

Even with the change, it proved to be a big year for both of the new MJHL clubs. Several players showed up early for Brandon’s training camp that season, which helped the team become incredibly close knit.

“We pretty much just stuck together and supported each other,” Spratt said.

The Wheat Kings played in the Wheat City Arena, which was built in 1913 and demolished in 1969. Spratt, who called the building “old and unique,” said the Wheat Kings were certainly well supported by the community.

“I don’t think I ever saw it not packed,” Spratt said. “They were truly — I say this because they were real hockey fans — it was a great, great town to play hockey in. They were very supportive and I had a great billet for the two years I stayed there and they were hockey-crazy people. They just loved the game and loved their Wheat Kings. You couldn’t ask for a better city to play hockey in.”

In the 1966-67 season, the Wheat Kings went 47-9-1, finishing second behind their former SJHL rivals, the Flin Flon Bombers.

“We were a really, really close-knit team,” Spratt said. “We were a powerhouse. We were strong from goaltending all the way out.”

Spratt was certainly a big help. The overage rearguard’s offensive contributions exploded as he posted 19 goals and 20 assists in 55 games, leading the defensive corps.

“I came into my own as far as confidence was concerned,” Spratt said. “I had good coaching, I had the support of the guys.”

He remembers scoring his first hat trick, earning a fedora from a downtown men’s clothing store, and Fairbairn quickly coming over to congratulate him.

“A lot of us on that team weren’t in the same league as Billy but whenever you did something unusual or you made a great play, those guys were always there to say ‘Great game’ or ‘way to go’ or ‘awesome’ or ‘where did that come from?’” Spratt said.

He said the key to his game was his skating, something enhanced by Dorohoy’s drills at practice. Spratt didn’t see a lot of power-play time, but found a way to contribute offensively anyway.

“Everything came together that year,” Spratt said. “Basically I built on the confidence and the support I had from the rest of the guys on the team.”

In the playoffs, the Wheat Kings beat the St. James Braves 3-0 in the quarterfinals, and then got past the Winnipeg Rangers 4-1 in the semifinals.

The Bombers, who had received a semifinal bye, were waiting.

Brandon’s northern foes, coached by Paddy Ginnell and starring Bobby Clarke and Reggie Leach, ultimately prevailed 3-2 in the best-of-five final to win the Turnbull Cup.

“Every game we played, because of the talent on both sides … we both wanted to win so badly,” Spratt said. “You just never stopped. The moment the puck was dropped, the war was on. That was the way every game against Flin Flon turned out. It was great, great, great hockey.”

Spratt didn’t want to leave after the season ended and he had graduated from junior hockey, so he stayed in Brandon for a while that summer working for the city as a lifeguard at pools.

“I would have stayed in that city,” Spratt said. “That’s how much I loved it.”

Eventually he headed home to North Battleford, learning in July he had been invited to New York Rangers camp when he received letters from assistant general manager Jack Gordon and coach Emile (The Cat) Francis. He was also given a signing bonus.

For a young guy who had watched countless games on Hockey Night In Canada, it was a real treat to find himself in camp with the Rangers.

Spratt, who played at five-foot-eight and about 190 pounds, walked into the Rangers dressing room in Fort Erie (Ont.), which in the Original Six era of the NHL, meant recognizable faces everywhere.

“The guy I was sitting beside was Orland Kurtenbach,” Spratt said of the six-foot-two Saskatchewan product who played 639 NHL games and later coached the Vancouver Canucks. “For a young guy like me to look up at this monster and think that I had arrived and this was what my destiny was … I was just awestruck. I’m not going to say I excelled by any means but I think I was not ready for that because it was a big jump.”

Spratt had already been approached by Fred Creighton of the Eastern Hockey League’s Charlotte Checkers, and had a pretty good sense he wasn’t sticking with the Rangers. He headed down to Charlotte to make the princely sum of $140 per week.

He had a good season, putting up nine goals and 18 assists in 59 games, with 67 penalty minutes.

“Now all of a sudden I realized it was a business,” Spratt said.

One of the four guys he lived with was former Wheat King Ken Hicks, which was nice, but it was a tough league. He returned the next season but after a handful of games, Creighton wanted to send him to the Eastern Hockey League’s Long Island Ducks.

Spratt wasn’t interested.

“I had pretty much assessed my ability and I didn’t want to stay in the Eastern Hockey League,” Spratt said. “I knew a few guys on that hockey team but I’m still a young man at the time. I knew I could bounce back and forth in the Eastern Hockey League and maybe get a crack at the International (Hockey League) or Central. When I walked into the office and Fred said ‘You’re going to Long Island,’ I said ‘No, I’m going home. I’m going to start doing something. I don’t want to spend the rest of my life down here. I’m going back to Canada and starting a career in something’ because I figured if I stayed down there for another eight or 10 years — I could have stayed down there that long based on what I saw as far as talent — but I thought that’s eight years when I can get a career and be in business doing something that eventually I would be proud of.”

More than 50 years later, Spratt stands by what he decided, even if it wasn’t easy.

“At that point in time, your emotions are running pretty high because you love the game,” Spratt said. “You want to play, but you know you have to make a decision.”

He had seen the guys in their thirties with families who were desperately hanging onto the game, and didn’t want to one day be in their shoes.

He headed home to North Battleford, joining the local intermediate team and starting a job with Canada Post. He later joined his father in his optical business manufacturing lenses, learning the specialized trade of grinding lenses and inserting them into frames.

He married wife Barbara four years after he returned to North Battleford, and they moved to Edmonton soon after, where she was going into nursing. They spent a few years in the Alberta capital, with Spratt opening up a plastics department in the optical company he worked for as they made the transition from selling only glass lens.

They had daughter Melissa in Edmonton, and then moved to Coquitlam in 1977, where Spratt started into sales in the industry and son Greg joined the family. He retired five years ago after working a day per week for a few years and enjoys time with his two grandchildren.

He swims and is a devoted bicycle rider, occasionally heading out with another former Wheat King, Vaughn Karpan.

“I took to it like duck to water,” Spratt said. “I love it. I was able to join a cycling team out here, which I rode with for three years. That’s where I hooked up with Vaughn, which for both of us was a great day. We’ve been good friends ever since.”

Sprat, who rides about 800 to 900 kilometres per month, has competed in half-Ironman races, half marathons and one full marathon.

Aside from a work ethic, Spratt took numerous lessons from the game, including a compulsion to always be on time and much more.

“Hockey for me was a real life lesson,” Spratt said. “It taught me a lot. The personality that I have today and the way that I connect with people I think has a lot to do with hockey. I have a respect for the job and want to do the best I can, which is what I did when I was out on the ice. Whether it’s on the job or anything I do, I want to do the best I can and I think it’s all related back to my hockey career.

“I think hockey made me who I am today.”